Bermanism

With Mario Giampieri, Kelly Leilani Main, Juncheng Yang, and Yue Wu

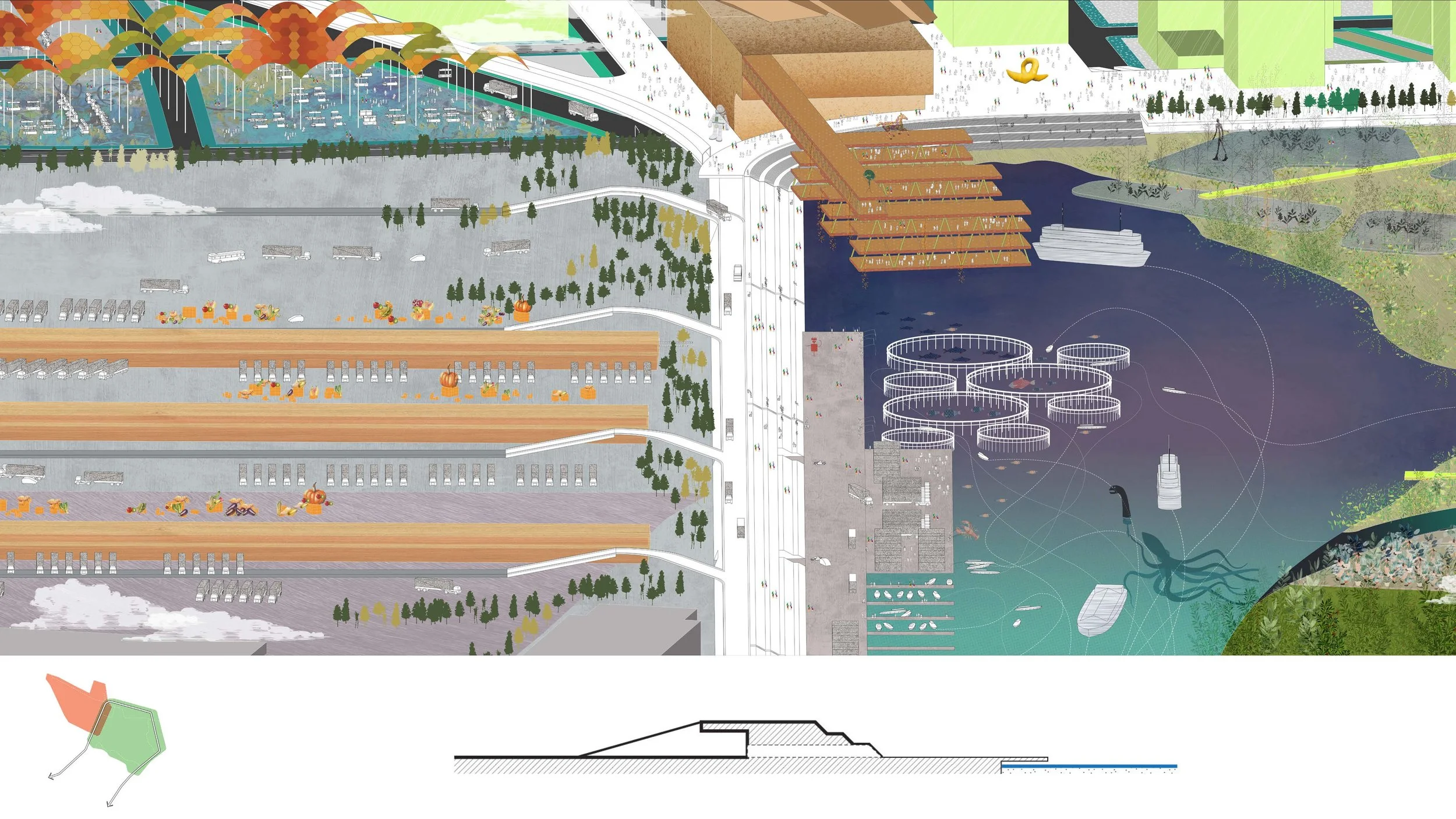

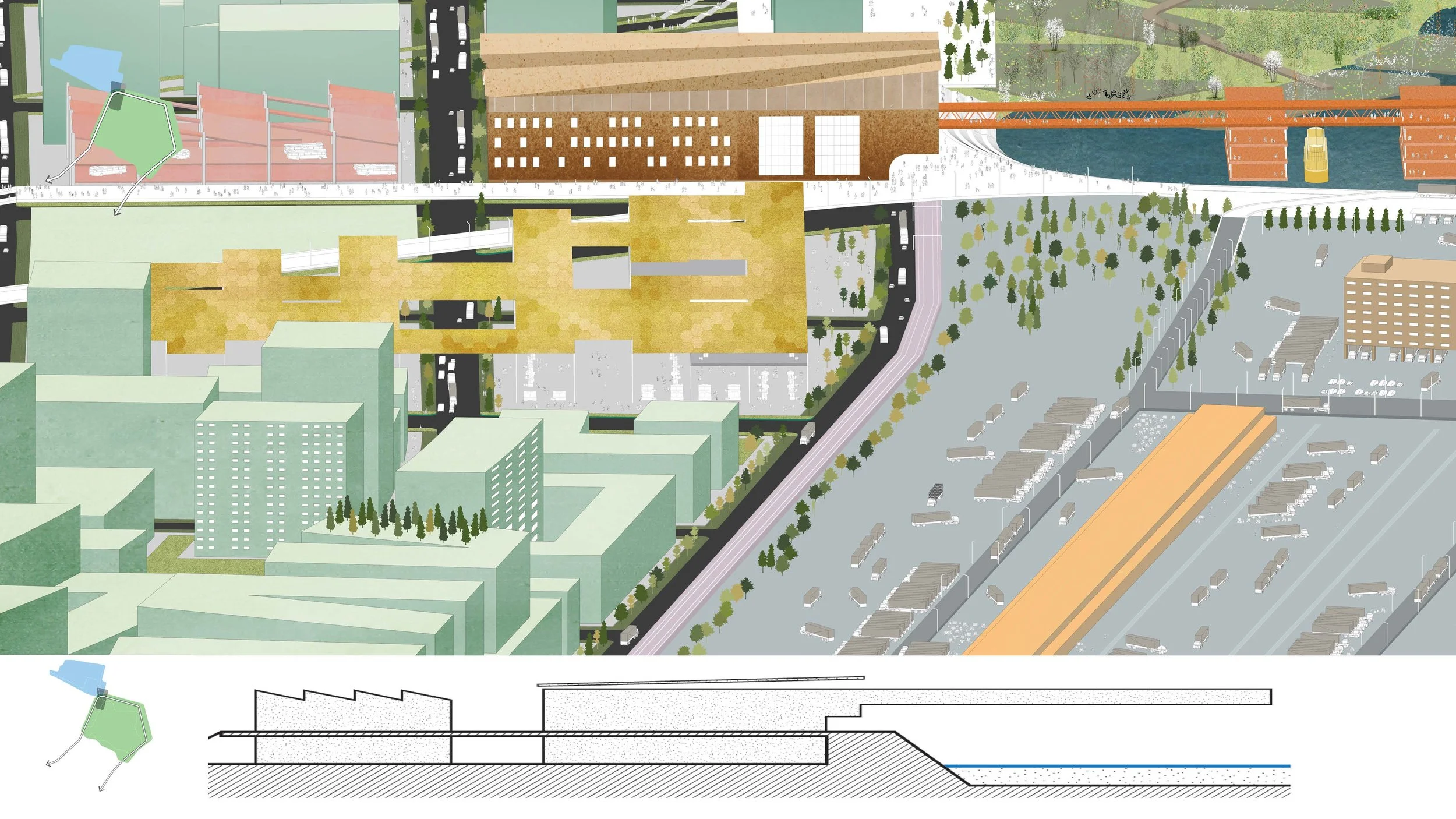

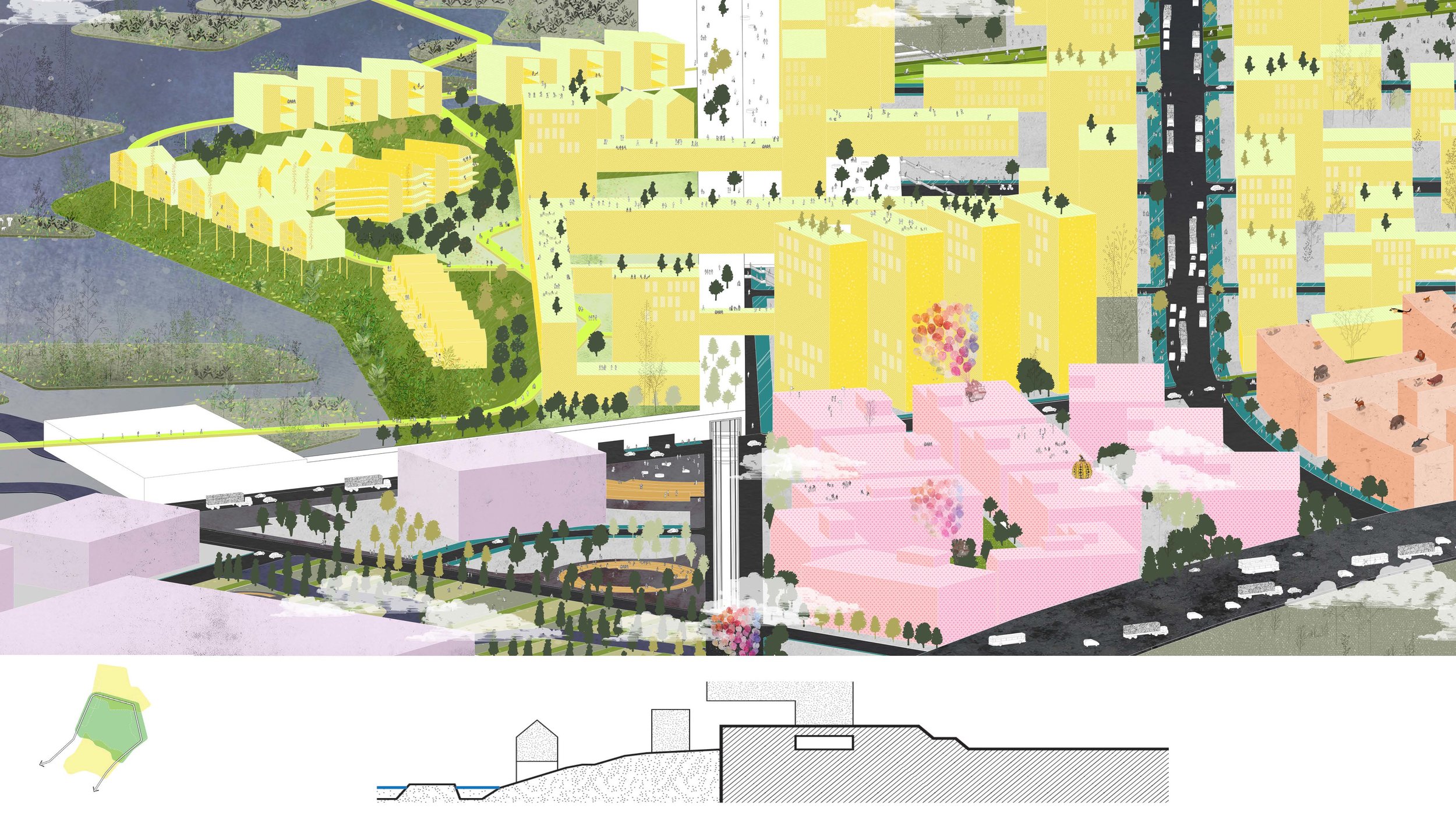

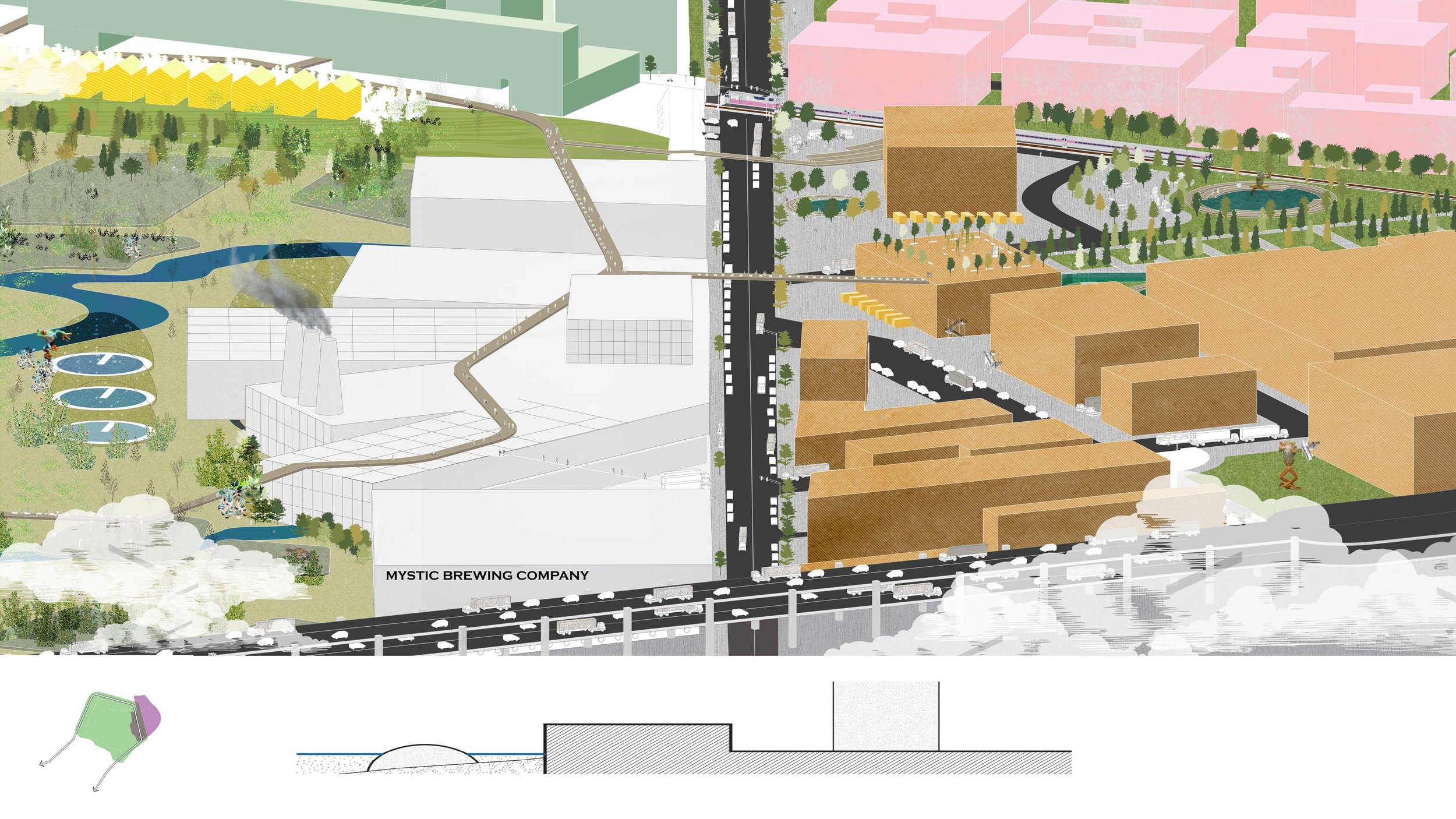

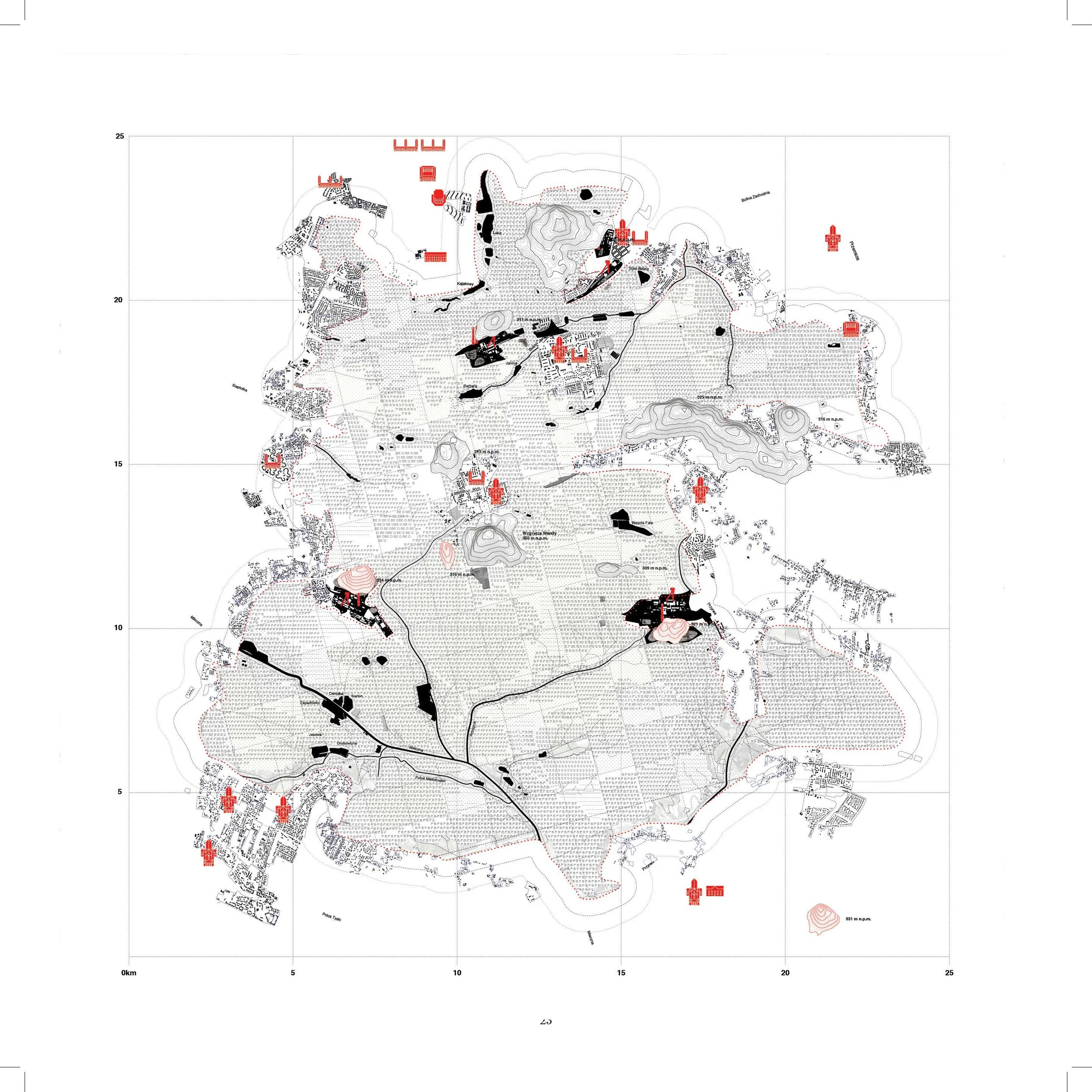

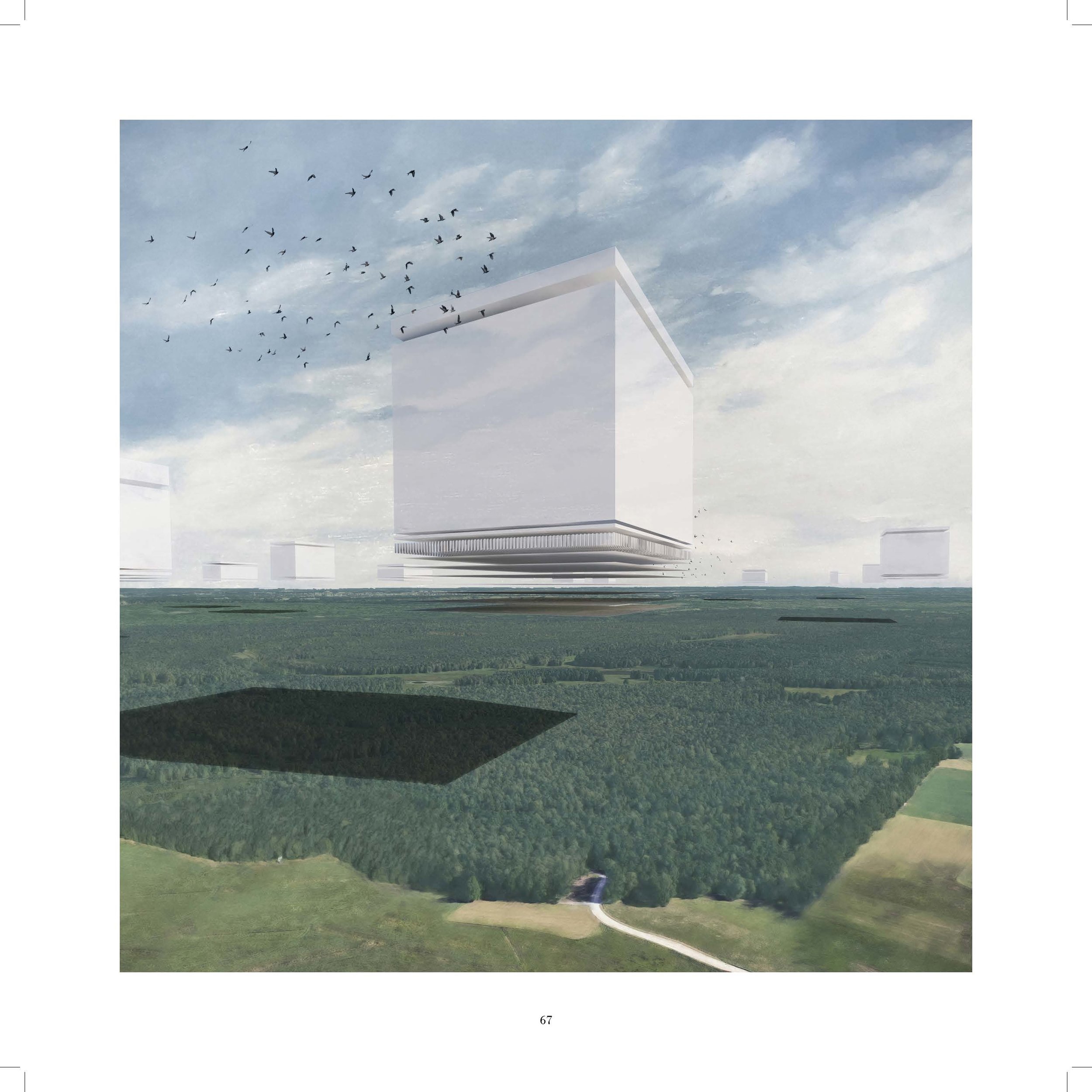

Chelsea, MA is an industrial waterfront town near Boston, MA. As a predominantly minority and predominantly industrial city, Chelsea is faced with a host of environmental problems, stemming from years of industrial activity that have polluted the water and the air. Essential transportation networks such as highway 1 and the T line provide access between other metropolitan cities in the area and Boston’s city center, but they cut Chelsea into disparate parts, impacting connectivity and fragmenting the urban fabric. West Chelsea, which also includes parts of the neighboring town of Everett, is located in the area to the West of Highway 1, and bears the brunt of this industrial legacy. A host of scattered industrial elements include the Mystic Power Plant, Distrigas Oil and Gas Storage the New England Produce Center, and other light and medium industrial and commercial functions, all of which share this space with public institutions such as hospitals and schools. These industrial functions all have priority access to the Chelsea Creek and Mystic River fronts, disconnecting residents of the city from one of their most essential assets: the water. But access to this water also has its own risks. This industrial area is the most vulnerable to sea level rise and pluvial flooding, located in the infill of the historic Island’s End Creek. Without proper attention, this area faces serious flooding hazards. But rather than reduce Chelsea’s coastline with a barrier at the entrance to Island End’s Creek, as many resiliency initiatives may suggest, we pose a different question: what if we expand the coastline, and invite the water in? To determine the extent of floodable area, we identified three pieces of critical infrastructure: the New England Produce Center, the T LINE commuter rail, and Everett Avenue. To protect these three critical areas, we propose returning a large-low lying swath of Industrial land to coastal use and creating a multi-functional berm which emphasizes connections between the now protected and floodable sides of the city. Protecting these three pieces of infrastructure results in positive externalities. Over time, the floodable area can be transformed into a coastal wetland, a green space that provides recreational and leisure opportunities for residents and visitors alike. Unlike other berms, we believe this strategy describes a new urban condition we call 'bermanism'. 'Bermanism' is “the utilization of a berm not to protect as much land as possible, but as a strategic marker which differentiates areas of upzoning (increased urban intensity) with areas of downzoning (return to green space and recreational use). As a marker, the berm functions as the primary access point by which floodable areas are connected to those that are protected by its existence. This process of upzoning and downzoning support four critical hingepoints along the berm; creating opportunities for new functions and integrated programming between floodable and protected. Together, these components form a cohesive whole, connected by the berm, where before there were only scattered elements. Together, they create a new form of urbanism which dramatically improves the quality of life in Chelsea.

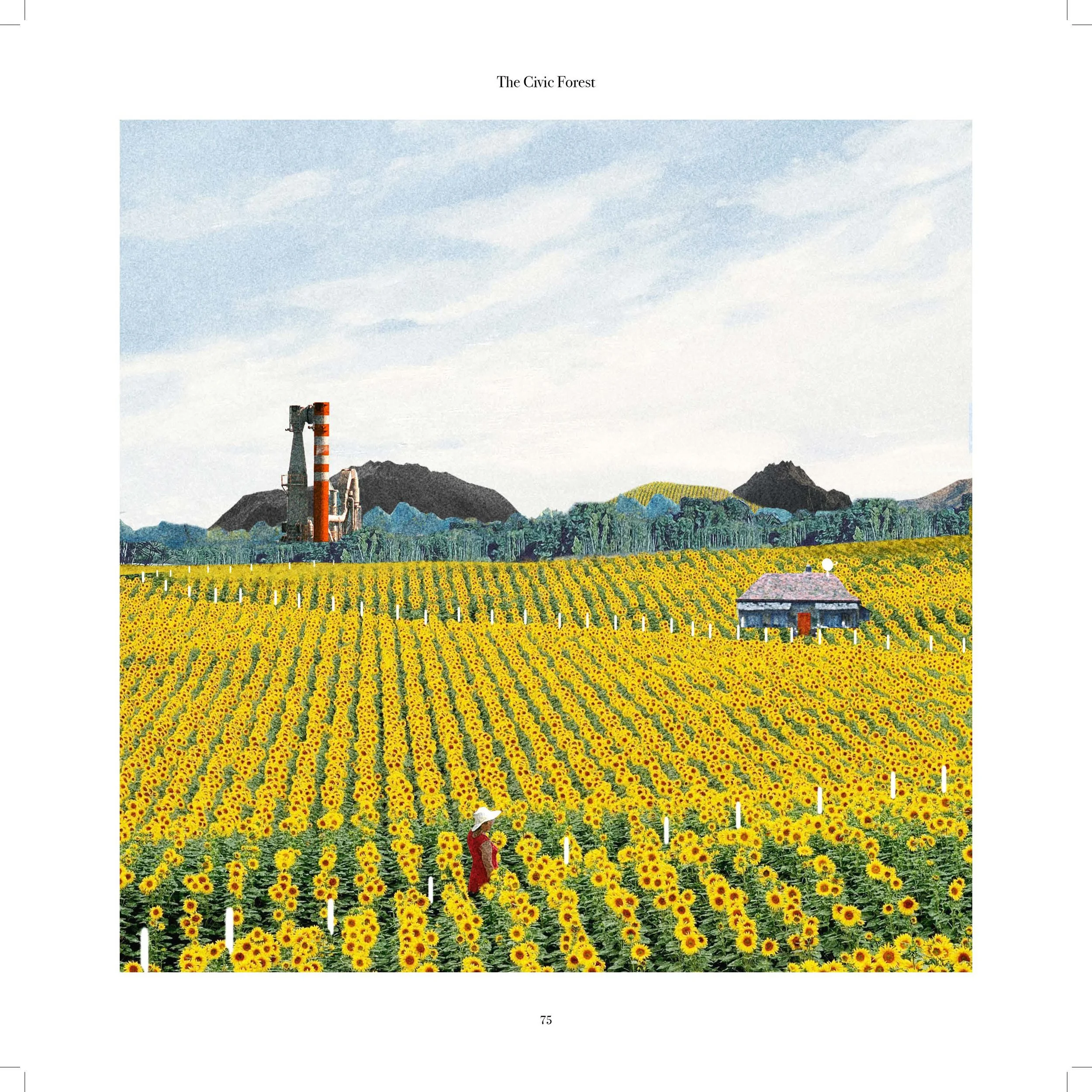

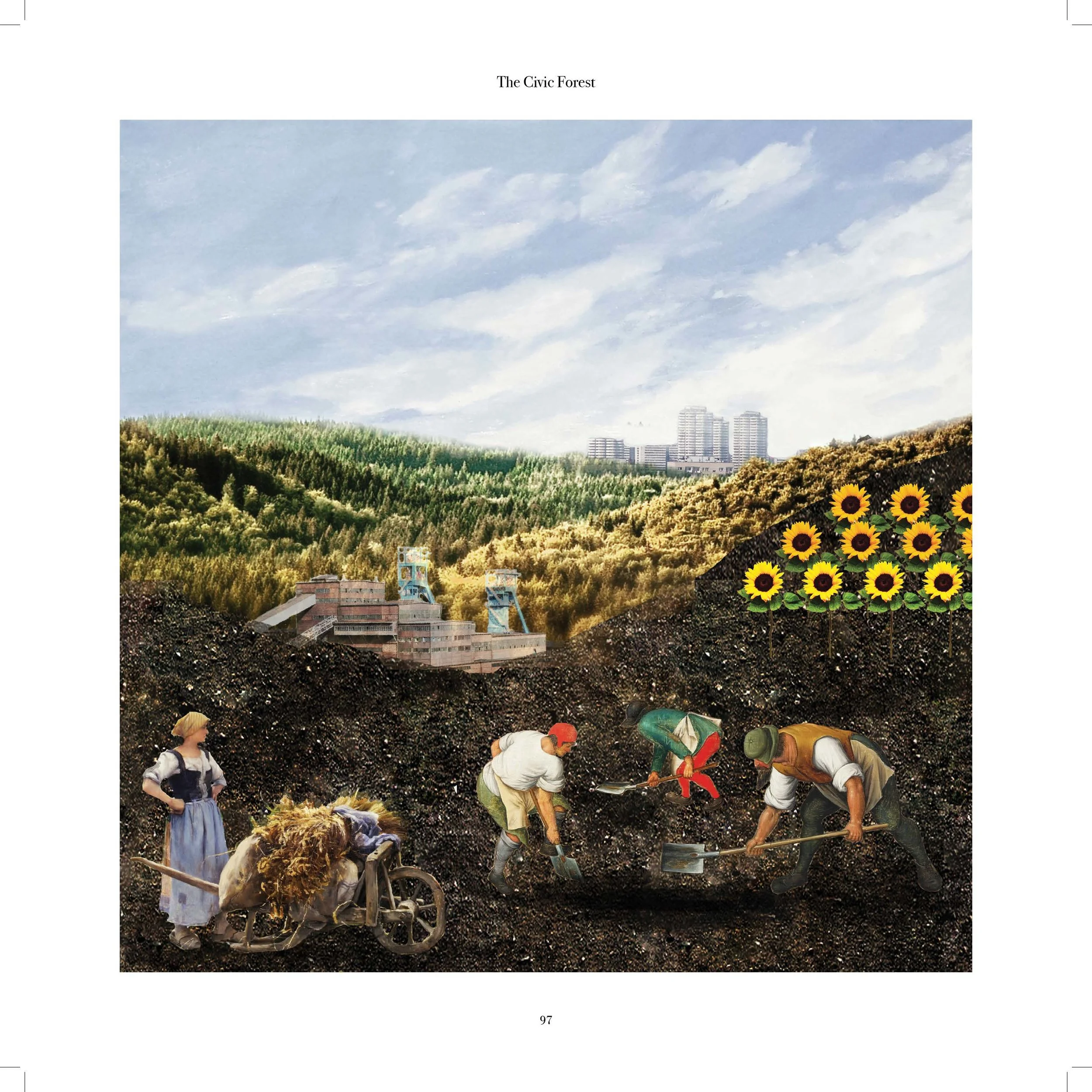

The Civic Forest

With Diana Ang, Giovanni Bellotti, Kelly Leilani Main, and Alexander Wiegering

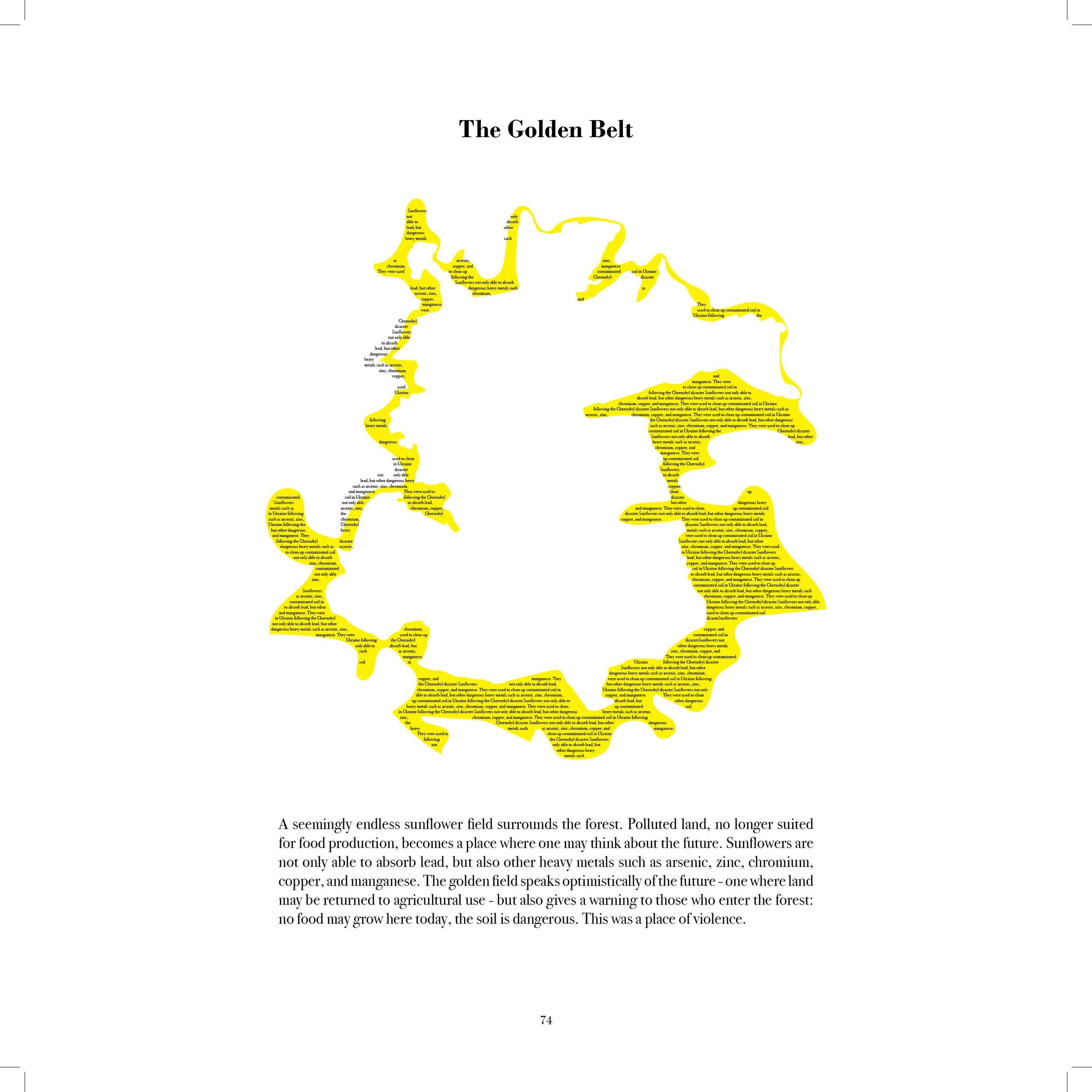

Silesia developed during the twentieth century mainly through the economy of coal. As new mines were opened, worker's settlements followed along with infrastructure and services. Its grown produced what we read today as a dispersed metropolitan area, where scattered industrial and extraction facilities are connected through railroads and motorways, where woodlands and water bodies exist as islands, framed by a low density, fragmented" city". As coal extraction drove urbanization, housing followed in a relation of mutual dependence with mines and industry. Today, while the metropolitan area sets itself to gradually transition to a post extraction economy, the traces of coal mining and consumption remain clearly visible on the ground, not only in housing and industry, but in the soil, the plants, and the water. Emissions of sulfur dioxide, deposits of heavy metals in the ground, and terrain subsidence due to mining have affected the acidity of the soil and the topogrnphy of the land, transforming over the span of 50 years the vegetation and the form of the region. Conifers were replaced by deciduous species; new water bodies appeared as a consequence of soil subsidence; farming for edibles became impossible. The current definition of "forest" as areas mainly occupied by hard wood species determines perimeters and boundaries subject to common vegetation patterns. According to this definition, forests in Silesia account for thirty percent of land cover, mainly located on publicly owned land. This reading, however, fails to define the forest as a political space, a component of the Silesian metropolis rather than its counterpart. We propose to address the forests of Silesia as new centers, capable through their scale and complexity to speak of the current problems and ambitions of the metropolis. The Civic Forest frames the collection of Silesian forests as a civic space; a space charged with a human agenda - environmental, economical and social - where to address ambitions and frictions between preservation, production, and extraction, through which to imagine new relations between domestic, productive, and protected spaces.